In the classic movie “The Shawshank Redemption,” there’s a moment where Andy Dufresne dreams of a life beyond the prison’s walls, symbolizing the power of hope and ambition against all odds. This beautifully mirrors the scenario faced at COP28. Just as Dufresne faced the formidable walls of Shawshank, world leaders at COP28 set ambitious targets to escape from fossil fuels in a “just, orderly, and equitable manner.”

The Dubai Consensus marks a pivotal moment in the history of climate agreements. For the first time since the inaugural COP in Berlin in 1995, there’s an explicit reference to fossil fuels and the need to transition away from them to halt global warming. Previous agreements have broadly referred to just reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This general approach persisted until the 26th COP in Glasgow in 2021 when a more specific commitment was made to address the most polluting of fossil fuels, coal. There, nations consented to a gradual reduction in its usage. The Dubai Consensus, however, has also recognized the need to triple renewable energy capacity globally by 2030 and accelerate efforts toward the “phase down of unabated coal power.”

Achieving these ambitious goals is undoubtedly a daunting challenge. The deep-rooted dependence on fossil fuels, the disparate economic strengths of nations, particularly those in the developing world, and the hurdles presented by existing technology create formidable barriers. Like the imposing walls of Shawshank, they are seemingly insurmountable yet not entirely impervious. The path forward is difficult but not unattainable, demanding perseverance and concerted global effort.

The journey toward phasing out coal presents three significant challenges, particularly for developing countries.

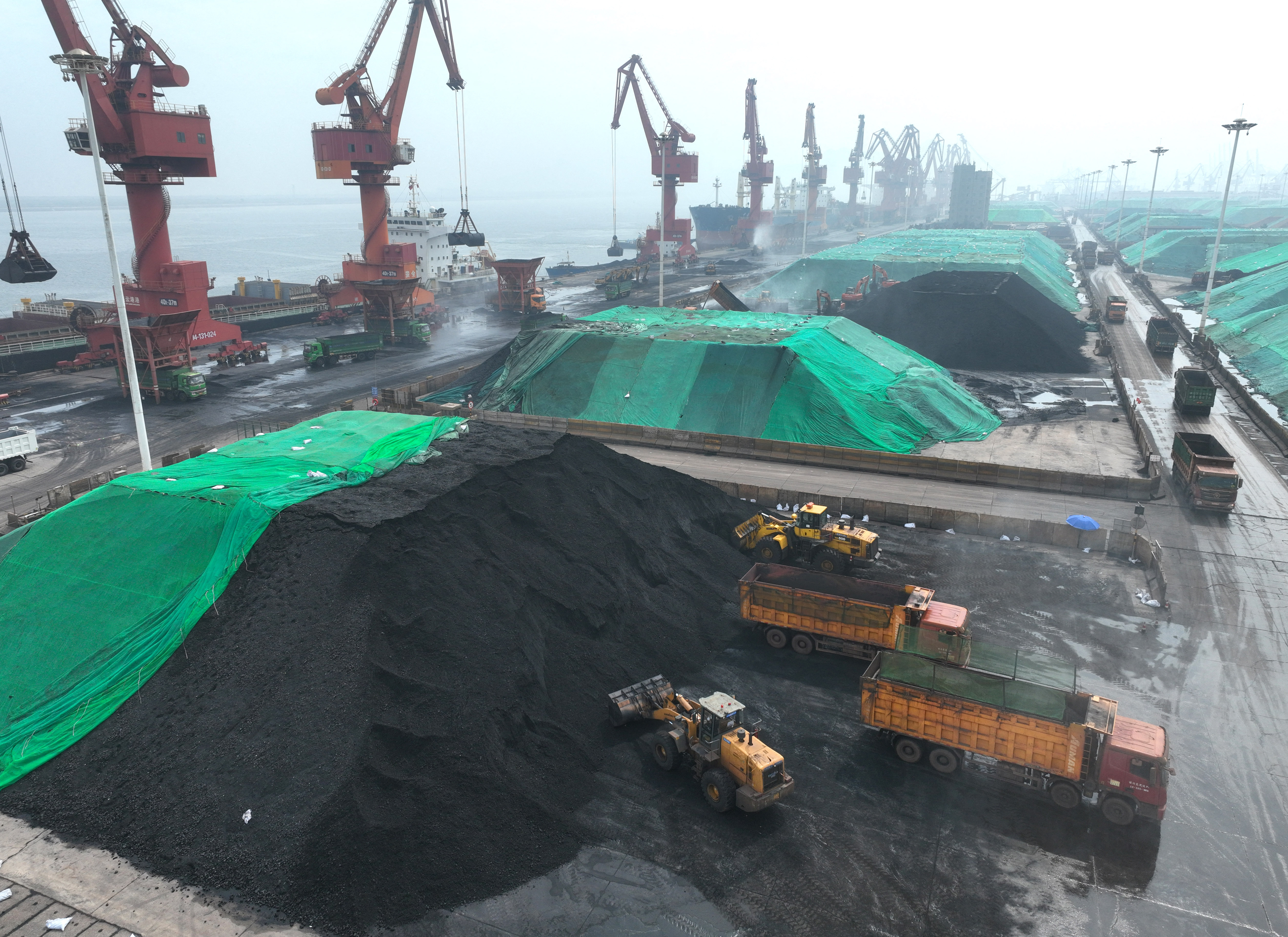

The first concern is energy security. Phasing out coal is a complex task; it currently accounts for approximately 26 percent of the world’s energy consumption. Notably, 81 percent of coal used in energy production is in countries outside of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, indicating that it’s predominantly developing nations relying on coal to meet their energy needs.

Consequently, eliminating coal usage substantially threatens their energy security, placing the onus of the transition away from fossil fuels on these countries. However, the lack of affordable and clean alternative energy sources and difficulties in technology transfer make this transition particularly challenging.

Second, a rapid transition away from coal could exacerbate poverty, particularly in regions within developing countries where coal is a critical economic pillar. Many developing countries have states or provinces that depend heavily on coal for revenue and employment. A swift phase-out could disrupt these economies, leading to increased poverty and socio-economic instability.

Further, the costs of energy transition in developing countries often directly impact household budgets. These measures can lead to higher costs for electricity, water, and transportation. The increased expense can be particularly burdensome in countries where a significant portion of the population already struggles with economic instability. While these policies are crucial for long-term environmental sustainability, their immediate financial impact on households in developing nations poses a significant challenge. Therefore, the transition needs to balance environmental goals with economic feasibility and the socio-economic well-being of the populations most reliant on coal.

Developing countries often argue that global discussions on reducing fossil fuel usage disproportionately focus on coal instead of equally addressing oil and natural gas. These nations, with significant coal reserves and a heavy reliance on coal for their energy, see the rapid phasing out of coal as a risk to their economic stability.

Moreover, there’s a sense of inequity in how developed countries, traditionally large coal, oil and gas consumers, advocate for diminishing coal usage – a vital energy source for many emerging economies. While the coal usage of OECD countries has declined, according to the Statistical Review of the World Energy 2023, oil consumption by OECD countries increased by 1.4 million barrels per day in 2022. This viewpoint suggests a bias in international climate negotiations, advocating for a more balanced approach that equally considers the reduction of all types of fossil fuels.

A third challenge for developing nations in transitioning to clean energy is access to capital and financing. The UN Environment Program’s Adaptation Gap Report estimates these countries need $215–387 billion yearly until 2030. The Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance’s second report reveals a stark reality: only 7 percent of 2022’s clean energy investments were in low and lower-middle-income nations (except China). These countries face daunting barriers like high-interest rates, vague policies and expensive capital.

To achieve the Paris Agreement, a substantial boost in renewable energy is crucial for emerging markets and developing countries. The key lies in a fivefold increase in concessional finance by 2030, as this is the most crucial yet scarce funding source for pressing needs. Developed nations must triple their bilateral concessional contributions by 2030. However, the scale of need surpasses what official development assistance can provide.

Similar to Shawshank’s formidable barriers, these obstacles make the path forward extremely challenging but not impossible. Addressing these hurdles is crucial, for without overcoming them, the transition will remain as elusive as Andy Dufresne’s dream of freedom within the confines of Shawshank.

Aditya Sinha is an Officer on Special Duty, Research, at the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India. X: @adityasinha004